What is there left to say about Dejan Lovren? Depending on who you talk to (or perhaps when you asked them), he is either a commanding and organised centre back, capable of perhaps one day captaining his new club Liverpool, or one of the biggest defensive transfer flops in Premier League history, the man at the heart of everything wrong with Liverpool’s back line this season.

The rise and subsequent plummet of Lovren’s reputation in England is really interesting to me, and I think it speaks a lot more for the argument that it is important to assess the defensive setup of a team as a whole before committing to spending big money on just one link in that defence. You wouldn’t put a slow, cumbersome forward up top for a team playing fast technical football, so why wouldn’t you profile your defenders in the same way?

This isn’t to suggest that Liverpool haven’t done their homework- I’m absolutely certain they have, with a statistical approach far superior to what I could achieve here, and with a level of information us bloggers can only imagine. What I want to understand is how Dejan Lovren performed in the context of the systems being used at his previous clubs, Lyon in 2012/13 and Southampton in 2013/14. Are there systematic differences in the way these teams were set up that can account for why he looked so great at Southampton and so poor at Liverpool?

In this first post, I’ll look at his final season at Lyon.

Lovren at Lyon: 2012/13

Under reported interest from Chelsea, a 20 year-old Lovren signed for Lyon back in 2010 for roughly £7.5 million. Shunted around the back four and often left benched, a reputation quickly developed of an unreliable defender, prone to costly errors and severely lacking in discipline; he was sent off an astonishing 7 times for Lyon, including 3 times in his final season.

In this final season, Lovren was first choice when fit for the most part. He played at left sided centre-back, establishing a partnership with newly signed Serb Milan Bisevac, a defender with plenty of Ligue 1 experience.

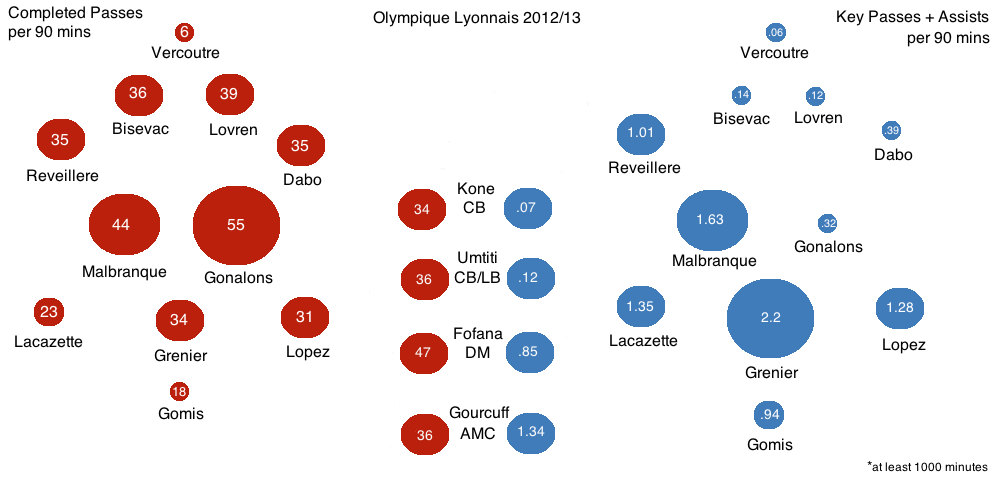

Lyon can broadly be described as playing a 4-2-3-1, with Maxime Gonalons sitting in front of the defence and Steed Malbranque playing box-to-box. Lisandro Lopez and Alexandre Lacazette appeared on either wing, with Clement Grenier playing at No. 10 behind Bafetimbi Gomis. Lyon spent much of the season near the top of the table, but fell away badly in March, losing 3 matches in a row, and eventually finishing 3rd.

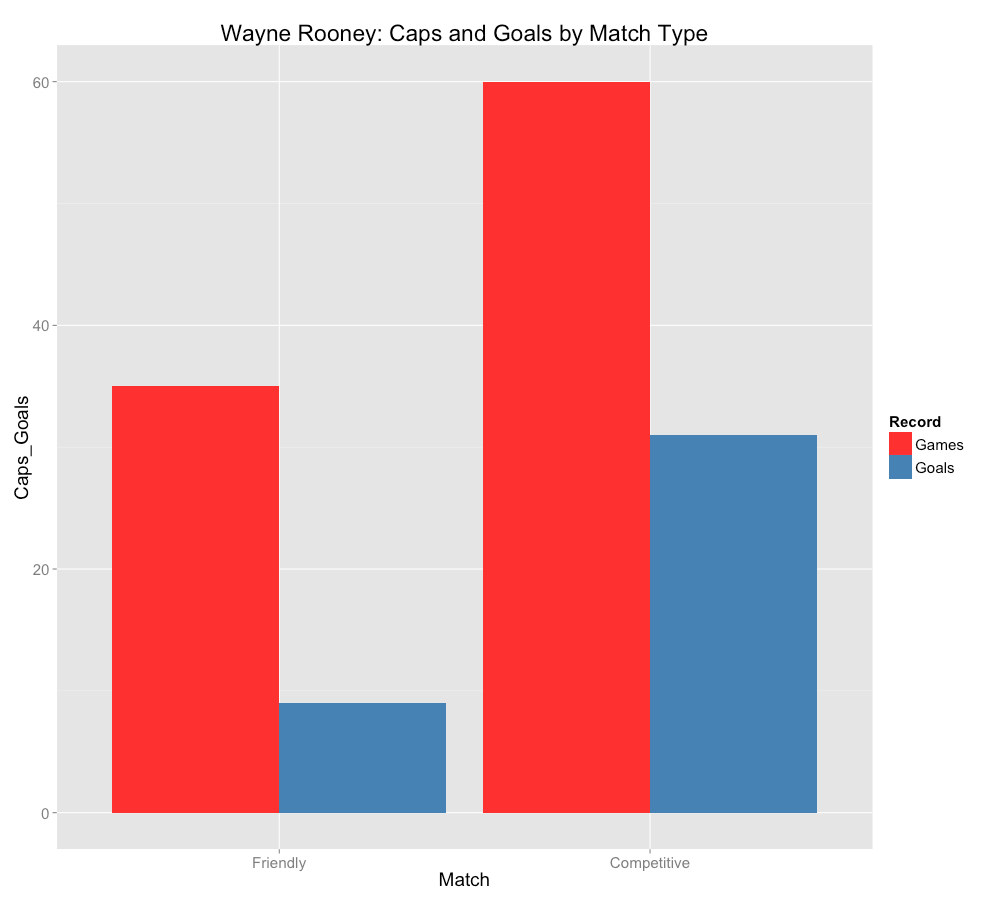

Most of the passing seems to go through Malbranque, Gonalons, and Grenier, with neither Anthony Reveillere nor Mouhamadou Dabo hugely involved from full-back. In terms of generating shots, Lyon’s right hand side is more active than the left, geared around getting the ball to Gomis in the box. Lopez also played up front at times, weighing in with 11 league goals to Gomis’ 16. Goalkeeper Remy Vercoutre appears to have bypassed the central defence with much of his passing, recording 13 long balls for every 3 shorter passes per 90 minutes.

Most of the passing seems to go through Malbranque, Gonalons, and Grenier, with neither Anthony Reveillere nor Mouhamadou Dabo hugely involved from full-back. In terms of generating shots, Lyon’s right hand side is more active than the left, geared around getting the ball to Gomis in the box. Lopez also played up front at times, weighing in with 11 league goals to Gomis’ 16. Goalkeeper Remy Vercoutre appears to have bypassed the central defence with much of his passing, recording 13 long balls for every 3 shorter passes per 90 minutes.

So, what can we learn about Lovren from these figures? For me, two things really jumped out. Firstly, Lyon always had at least one deep-lying midfielder hanging around in front of Lovren and Bisevac. Gonalons was pretty much constant throughout the season and, as I’ll show in a moment, did a great deal of defensive work. Steed Malbranque was enjoying an unlikely revival as an all action midfielder next to him, weighing in defensively as well as helping Lyon create chances. Gueida Fofana, another defensive midfielder, often appeared alongside Gonalons, meaning the Lyon midfield did plenty of defensive work shielding Lovren and Bisevac. Secondly, Lovren’s regular fullbacks (typically Mahamadou Dabo but sometimes Samuel Umtiti) were both fairly conservative, not hugely involved in attacking play.

What about in terms of defensive actions? Where does this team win the ball back, either through tackles or interceptions?

These figures help to clarify Gonalons’ role- he was by far the greatest contributor in terms of tackles and interceptions and rarely got himself up the pitch in a creative capacity (17 shots, 11 key passes and 0 assists all season). Lovren and Bisevac were thus pretty well shielded, each making just 1 tackle per game.

One very important thing these stats don’t tell us is how Lovren positioned himself during opposition attacks. His role at Southampton as an organiser, cajoling Jose Fonte and urging his full-backs up the pitch, is rarely in evidence whilst watching footage of Lyon in 2012/13.

I’ve watched this attack develop a dozen or so times, and each time I’m left a little more baffled by Lovren’s decision making.

First of all, this shouldn’t be a dangerous situation. Lorient are in possession with two attackers completely surrounded on the right flank by Monzon, Lovren’s fullback, Gonalons, and Grenier. There is no need for Lovren to get sucked in like this, and he leaves Bisevac completely isolated.

Now Lyon are in trouble. Monzon and Lovren have both moved towards the ball even further, and Lorient break down the right. At this point, Lovren has essentially put himself out of the game. Bisevac is perhaps at fault for not sticking to Aliadiere tightly, but he has to move across in case Monzon gets dribbled past.

A complete lack of communication with Umtiti in this example means Lovren does not even attempt to challenge for the header, presumably assuming Umtiti will go for it instead.

And from the same game (skip to 2.10), Lovren is about 5 metres further forward than Bisevac, and then gives away a penalty.

Skip to 2.07 in that last video, and see if you can see Lovren as Nice attack. He’s certainly not at centre-back, next to Bisevac, where he should be…

That’s because Lovren has rushed ten years ahead of his defensive line to attempt to win the ball back. Dabo has moved centrally to mark the guy who should be Lovren’s responsibility. When Lovren fails to make the tackle, he turns around, but still doesn’t seem to realise just how far he is from Bisevac.

Dabo has gone to intercept the cross, leaving the guy he was marking completely free in the box- Lovren makes no effort to get back into shape, and luckily for Lyon the shot is pretty much straight at Vercoutre. Watch the next highlight too- Lovren completely ignores the fact that Cvitanich, Ligue Un’s joint 2nd top scorer at the time, has just pulled off his shoulder- he is ball watching again. At 3.20, on a yellow, he dives in to a challenge fully 50 yards from his own goal and gets sent off.

There are also some noticeable examples of Lyon being completely undone at the back by speculative or aimless balls from deep towards Lovren’s side.

(skip to 1.34 for that last video)

When I watch these three clips in particular I recognise the Lovren we sometimes see at Liverpool- struggling one versus one and a certain level of panic around his game, which results in poor decision making.

The Lovren we see at Lyon is a proactive defender- he seems to prefer moving towards the ball whenever possible. When this comes off, it looks great- a centre-back racing out of defence to win the ball in midfield. When it doesn’t work, however, a huge gap is left behind Lovren, and his lack of communication with his full-back and with his centre-back partner Bisevac is often noticeable. Whether what we see here is the naivety of a young centre-back, or an inherently poor reader of the game, is more difficult to determine. It is a very stark contrast from what we saw the following season at Southampton, where Lovren was always pointing and shouting to his teammates. The stats suggested that Gonalons was a big contributor defensively, and its probably no coincidence that some of Lovren’s poorer moments appear to have come when Gonalons had been completely bypassed.

Lovren has spoken in the past about how his confidence was low at Lyon- he struggled to settle in at first, finding the language barrier particularly difficult to deal with. He speaks about the pressure the fans put upon him because of his high fee, and the idea that referees had typecast him as a dangerous and reckless tackler. Whether this is really true or not doesn’t matter, but it certainly suggests to me that Lovren is something of a confidence player, who cares deeply how he is perceived. It often seems to be the case in football that mistakes compound one another, and indeed a series of bad mistakes cost Lovren his place towards the end of 2012/13, the final straw being that goal conceded against Sochaux.

Anyway, more on this in a few days, when I’ll take a look at Lovren’s next season at Southampton.

Follow One Man Club on Twitter